Nearly every dancer remembers their first encounter with a professional in full costume. For non-dancers, imagine you’re five-years-old again and Glinda the Good has stepped right out of “The Wizard of Oz” to grant you a wish. It’s like that.

Nearly every dancer remembers their first encounter with a professional in full costume. For non-dancers, imagine you’re five-years-old again and Glinda the Good has stepped right out of “The Wizard of Oz” to grant you a wish. It’s like that.

I was in the elevator heading to a workshop show halfway across the country when Tamalyn Dallal stepped in wearing her full bedlah. Always gracious, she smiled and said hello and then we rode in silence while I stared at her. She went off to dance and I took my seat without realizing who’d joined me in the elevator. (I’d been dancing all of six months, so I was relatively clueless.)

Probably because I was so new to belly dance, I didn’t know what I was watching. I grew bored, especially with the folkloric stuff.

So did the radio DJ announcing the show. I was about to cut out to catch some jazz across town when the dancer from the elevator took the stage and absolutely killed it. The DJ grabbed the mic and yelled, “Now that’s belly dancing.”

That was 1998, I still get the same feeling every time I see Tamalyn dance.

Tamalyn began studying in the late ‘70s, but didn’t begin dancing professionally until six years later in 1982. For 39 years, she’s travelled the globe, performing and teaching in 41 countries.

We focused our talk specifically on how the dance has changed since the ‘70s, its explosive growth in China and Argentina and explored how the problems of colonialism are reframing how Tamalyn approaches the dance.

Musically inspired

Unlike many dancers drawn to the costumes or inspired by the performance of a dancer on TV or in the movies, Tamalyn was originally drawn to belly dance because of the music, taking the bus from her home in Kirkland, Wash. to the U-District near the University of Washington to buy LPs. Her collection included Eddie Kochak, George Abdo and Mohammed el-Bakkar’s “Port Said,” as well as several from Naif Agby.

That fascination with the music lead her to jump at a belly dance class even though she was only four weeks away from starting college in Arizona.

After she learned just enough for her college boyfriend to call her “his belly dancer,” she decided she’d better take more classes to properly earn the moniker.

Back then, her teacher taught from a syllabus of moves, working through them like working through a vocabulary list. It wasn’t long before the dancer cut Tamalyn loose suggesting that she find a new instructor since the teacher herself only had two years of experience.

Waiting to turn pro

Tamalyn’s first real performance, organized by her comparative religion teacher, happened after she’d been dancing for 10 months. She practiced mornings and evenings every day for three weeks, believing she needed to perform the full five-part routine no matter how many minutes she danced. She also worked in floorwork and backbends.

But it was six years before she went truly professional.

Today, Tamalyn says, students often are in a rush to go pro, but she enjoyed every bit of her journey. “It was a big thrill every little step of the way. Little by little, you get asked to be in student performances. Then to be in the workshop show,” she says. “It was fun being a student. That’s a great phase. I wouldn’t want to skip that.”

The tone of classes was much different in the ‘70s, she says. “some teachers were expected to be tough. Back then there was more sternness in the teaching and you could be scared of your teacher.” But Tamalyn stuck around. “I wasn’t expecting to be catered to. I was there to learn.” Now teachers can be friendlier with students, which is nice, she says, but there is more of a “consumerist expectation.”

After transferring to a college in New Orleans, Tamalyn found Habiba, who she says bore a strong resemblance to Jaclyn Smith from “Charlie’s Angels.” Habiba charged $10 a class in 1976. Adjusted for inflation as of April, 2015, that’s $38.73 a class, which was out of Tamalyn’s price range.

Recognizing her protégé’s talent, Habiba let Tamalyn teach warm-ups in exchange for lessons. “She’d take a lot more time trying to teach me how to teach than if she’d just taught the class,” Tamalyn says.

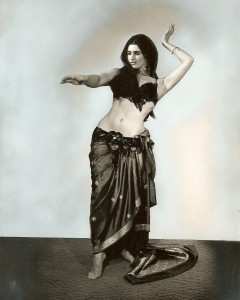

Tamalyn’s first video clip: 1982 (promo for doing bellygrams)

From beads to evening dresses

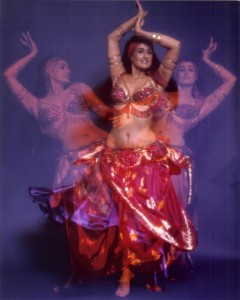

By the early ‘80s when Tamalyn started dancing professionally, costumes were already starting to shift. At the end of the ‘70s people were wearing lots of coin bras and belts, circle skirts and harem pants, she says. In the ‘80s that shifted to beaded fringe and straight skirts, but people were still making their own costumes. Tamalyn did a great deal of hand beading throughout the ‘80s. In the late ‘80s, foot-long fringe came into fashion. Her first costume imported from Egypt was “covered in beads.” That was 1993 and it cost $1,000, which would be worth $1,624.37 in 2015 dollars. In the mid ‘90s dancers started having access to lots of costumes from Egypt and Turkey. In the 2000s, the Dina bra and short skirt became popular along with cutouts.

Tamalyn, however, is pushing the other way. She’s dancing in evening gowns she modifies or makes herself, using color, contrast and well-placed crystals to draw attention on stage. This choice is influenced by her age, she says, but not because of body shame. She celebrates the comfort and freedom of dancing in long jersey dresses, wishing to be an example of how a dancer can be beautiful and sensual regardless of how much skin she shows. After years of performing a dance that is often not taken seriously by the general public, Tamalyn says she is personally striving for dignity and respect.

Changing dance styles

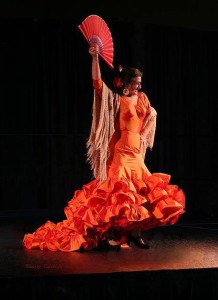

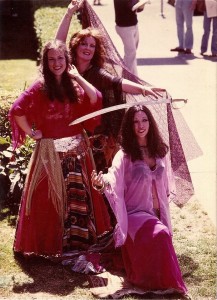

On the West Coast, Tamalyn says dancers decked out in coins, assyuit or striped fabrics found themselves influenced by Jamila Salimpour’s style. “Even when you didn’t do tribal, you were influenced by tribal.” When she moved to Florida in 1979 there was nothing tribal, but there she found a Lebanese-Canadian teacher who would invite students to her home for home-cooked Arabic food and dance video viewing. In the early ‘80s Tamalyn and her classmates gained exposure to Egyptian dancing through video, but travelling to Egypt was rare, except for the lucky ones that travelled with Morocco of New York. Now, she says, there are many belly dance festivals organized so dancers can go on their own. With political instability, poverty and increasing religious conservatism, work for dancers in Cairo’s hotels and clubs has dwindled, but the international passion for the dance keeps Egyptian dancers and teachers working at festivals, teaching foreigners.

After dancing all over the world, I asked Tamalyn to list what she thought had improved since the ‘70s. Technique, makeup and knowledge of the rhythms have all improved, she says, but “you can’t get as deep of emotion now because we’re doing little short shows. You can go deeper into your emotions when you have a half hour to 40 minute show. In the ‘70s you did go deeper.” Tamalyn was still to young to enter a night club, but while bussing tables downstairs at the Cedars of Lebanon Restaurant on Aurora Ave. in 1978, she “snuck upstairs to see Badawia, Dahlena and others as they transformed the atmosphere of any room they danced in. Whereas before, people didn’t talk about feeling; they just felt it.”

While many professionals miss the U.S. nightclub scene, Tamalyn’s travels afford her a different perspective. Dance is “exploding” in China, she says, taking off in the last twelve years, as well as in Russia, and now there are “thousands of dancers” in Argentina and Brazil (with the largest belly dance festival in the world, “Mercado Persa,” uniting 6,000 dancers a year in Sao Paulo). She also sees growth in many cities across the U.S. including New York and Miami.

Where she does see it struggling is possibly Europe, where it’s influenced by the economy and in the Middle East where it faces religious challenges. People say it is struggling in Seattle, despite its strong economy and large dance scene. But according to a recent survey, dancers get paid less in Seattle than in nearly every other city in the U.S. Tamalyn feels that if, collectively, people believe in themselves and believe in the dance and its potential, the dance can grow again. No longer is there just Egyptian, Lebanese, Turkish, old-style AmCab styles, but now there’s all kinds of tribal, Bellydance Superstars style, and also distinct Russian and Argentinian styles.

[soliloquy id=”377″]

Addressing cultural appropriation

All of this change brings a growing awareness of cultural sensitivity, but Tamalyn is cautious with the use of the word “appropriation,” preferring to leave the question of authenticity to the audience. “If you’re dancing at an Arabic wedding and they like what you do, you’re doing what they like. They’re getting their money’s worth. If it wasn’t authentic, it was what they want to see. If you try too hard to be authentic, it could be good, or you could be an imitation or character of their people and actually make people feel uncomfortable.” For Tamalyn, “being authentic is to be your most authentic self within the art form.”

From examining her own naïve interest in Orientalist art in the ‘90s, to reconsidering what she wears when she dances, Tamalyn says the hard part is realizing that even the aspects inspired by colonialism are “still art.” Rather than wholesale right and wrong, she advocates a personal increase in awareness and sensitivity as a way for each artist to find his or her own path.

For Tamalyn, that sensitivity is finding its expression, in part, in her costuming choices. “When I wear evening dresses, I feel like I can be as traditional or nontraditional as I want because I’m dancing the way that I dance, but I’m wearing something of my own style that is accepted by even the most conservative Middle Eastern audiences.”

Mainly, she says, “It’s what you do with the movements and how you use them that’s important and that takes a lifetime of study and experience and travel. And that’s the beauty of this dance. It’s a reflection of life experience.”

Choosing knowledge over innocence: Learning about colonialism

Deepening our knowledge of colonial history, may be the best thing for everyone, Tamalyn says. Especially when you realize that “maybe five countries in the world have never been colonies.”

“If we look at what colonialism is and how it continues to have this undercurrent around the world, then I think we can make educated choices about what we do with our dance. Not to feel guilty or ashamed about anything we have done in our dance, but we also can’t be so innocent either.”

40 Days and 1001 Nights

In 2004, Islamist militants abducted American Nicholas Berg in Iraq and beheaded him as part of their protest of the treatment of detainees at Abu Grahib. Tamalyn was scheduled to travel to Egypt for the “Ahlan Wasahlan” (Arabic for “Welcome) Festival, but in the U.S., everyone kept asking her if she still planned to make the trip. For Americans, it seemed, Islamic countries tended to blur together. Tamalyn happened to be traveling with her brother, Richard Harris, renowned travel writer and editor, in Wash. State at the time. While talking the situation through with him she came up with an idea that would completely alter her perspective on life and bellydance.

She’d make the trip to Egypt. If it proved to be safe, she’d go on to spend 40 days in five different Muslim countries, taking the time to “get below the surface.”

The festival proved safe and Tamalyn let go of her apartment in Miami Beach, moved to Seattle to spend more time with her elderly parents and planned to teach workshops between visiting each country to help finance the project. As she started traveling, she “felt strongly that people needed to see what I was doing.” She started filming with a small, hand-held camera she carried in her purse.

Before the 40 Days trip, Tamalyn was very strict about making sure that everyone in her troupe moved with synchronized precision. Now, Tamalyn says, “I’m opposite all that. Everybody matching perfectly is so the antithesis of Middle Eastern culture.”

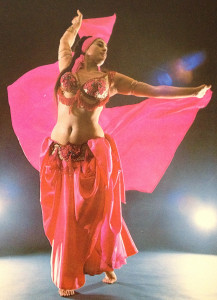

These days, she emphasizes the concepts of Earth and Sky, her six points in the body, relaxation and enjoying yourself. There is a groundedness to Tamalyn’s performance and teaching that can draw the eye in a room full of dancers. Her movements suggest a lifetime of a study and expression and after a workshop with her, you can see how she manages to transmit this to her students.

Tamalyn says coming to this new style has been process of shedding, “When you’re from one country and you live in different cultures, you really have to shed layers and layers of preconceived notions and we have a lot of layers drilled into us from the media. Coming from 21 years in Miami Beach, I was very focused on body and body shape and vanity and exposing your body. Being in different Muslim countries, it was nice to be beautiful, but it wasn’t attractive to show off your body. It wasn’t accepted. Living a good part of 2006 covering my body changed my perspective from ‘my body is my value.’ I had to find value in myself as a person rather than the superficial outer aspects of what I look like. As a woman, that’s a huge change in perspective.”

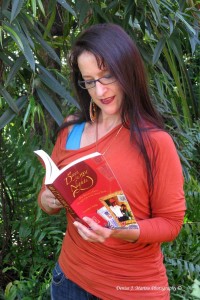

The “40 Days and 1001 Nights” book and film faced a “double-stigma” by addressing Muslim issues and belly dance, Tamalyn says. Eleven years earlier, her first book, “They Told Me I Couldn’t,” based on her dance adventures in Columbia had faced similar challenges.

With “They Told Me I Couldn’t,” bookstore owners would either refuse to take the book or hide it because there was a picture of belly dancer on the cover.

Although more than a decade had passed, Tamalyn faced similar challenges during her book tour through the back roads of the United States.

While she received strong support from various belly dance communities, Tamalyn cited several examples: A librarian in Raleigh, North Carolina was the only non-dancer at the showing. She hid in the back and finally admitted she was hesitant about watching it; a restaurant owner in another state agreed to show the film, but wasn’t comfortable confronting restaurant goers who were loud and rude during the showing and in Santa Fe, a bookshop owner claimed people weren’t going to be interested in seeing the film, although he allowed it to be shown. He stuck around, however, and liked it after all. The book remains timely, addressing much of the xenophobia current in the United States.

“Our perspective,” Tamalyn says,” is still very colonialist. We’re all people. We’re all just in this big world together.”

Lessons from Ethiopia

The most interesting lessons came from several visits to Ethiopia. After her brother became ill and passed away, Tamalyn went looking for some of the joy he was able to find in unexpected places – choosing Ethiopia, in part, because people “expect poverty” there.

But there’s nothing impoverished about Ethiopian attitude.

Although Ethiopia was occupied by Italy from 1936-1941, the country was never truly colonized. “They don’t look up to anybody,” Tamalyn says, nor do they feel the need “to look outside their culture. When you go someplace where no one is going to look up to you or anybody else, you think, ‘Hey, this is the way it should be.’

Global influence

While people in Argentina credit Tamalyn with introducing the sword dance, Turkish 9/8 and the “Zar” during the ‘80s and teaching finger cymbals in the early ‘80s, being an original member of Bellydance Superstars in 2003, afforded Tamalyn a truly global distribution of her art. “Bellydance Superstars did a huge service to all of our careers,” Tamalyn says. “You found those CDs in every single market all over the world. In many countries, that was the first introduction to belly dancing. In China it was, from the Bellydance Superstars DVDs.”

Countries beyond Tamalyn’s already impressive travel list started calling in 2007. Today, Tamalyn teaches regularly in Indonesia, Japan, Taiwan, Thailand, Argentina, the United States and holds a yearly month-long seminar in China that has included first-run performances in their brand-new theaters.

For dancers seeking a similar lifestyle, Tamalyn has the following advice: “Follow your passion and visualize what you want to do and it will probably come to you in different ways than you ever expected it,” she says. “If you love the dance, you follow what you need to do, not what other people are doing. If you teach dance to ten women in a tight-knit community where you change somebody’s life, that’s way more important than being famous.”

PRACTICAL QUESTIONS

How often do you practice? I’m guilty. I used to practice a lot and I love to practice and I recommend practicing an hour or two a day, five days a week. And I should practice more.

In the ‘80s, I practiced improvising to two sides of an LP or tape daily, most days of the week. In the ‘90s, I taught and did so many shows and conducted so many rehearsals that it was a treat for me to practice for my own shows. Around 2000, I started going to the gym two hours a day, five days a week for four years. Now I practice what I’m working on but what I recommend and what I find effective is to practice one to two hours a day, five days a week. Starting with a warm-up and slow moves, then covering shimmies, zils, free style, veil, practicing for shows and, finally, “iPod-shuffle” in which one dances to any kind of music that comes out of the iPod when it is shuffling. (The video below shows Tamalyn dancing to a song she’s never heard before.)

What’s the best piece of dance advice you ever received and who gave it to you? There was a tour guide in the Siwa Oasis in 2004 and they were playing some Bedouin music in the tape deck in the Jeep and the tour guide and the driver started dancing in a way that was very slow and sensual — the way that men dance in Siwa. It was much slower than the music and we started dancing how we know to dance. We were following the beat. ‘Slow down,’ he said. ‘What are you doing?’ And he’s going a quarter of the time and I thought he was crazy. He didn’t know what he was talking about, but I got that reiterated again in 2007.

Farafra Oasis in Egypt and there was a man dancing with strange wobbly legs and he was moving his hips in a crescent motion very slowly and most of the dancers went to bed because they thought the men were drunk. But I was fascinated.

The same year I saw private women belly dancing for each other in Kenya. On the tiny island of Lamu, they do Swahili, Indian and Arabic dance, and when they belly danced, they were moving much slower than the music and it was really in their body and it was really interesting. There’s really something to this. That was a really great piece of advice to slow down.

If you could whisper one piece of advice in every dancer’s ear, what would it be?

Enjoy.

LEARN TO DANCE WITH TAMALYN

Tamalyn offers regular workshops and performances worldwide. You can find out more about her upcoming events here, but a couple of especially fun ones are coming up this summer and fall. If you have the opportunity to study with Tamalyn take it. I’ve studied with her on and off for the last 17 years and have never walked away without learning something new and wonderful that immediately improved my dance.

Week-long intensive at Zamani World Dance near Seattle: July 15-22, 2015

Las Vegas Belly Dance Intensive: September 10-13, 2015

Month-long Intensive in China: September 29-October 26, 2015 (video from last year’s event follows)

Last year’s China theme — Water:

Dancers explored the nature of water crystals, inspired by the work of Masaru Emoto, who wrote the book “The True Power of Water.”

For this performance at a newly built city lakeside park, she’d intended to simulate iceskating to show “ice,” but the day was so lovely, that she adjusted to the location and “just danced.”

Here’s an example of a structured improv where each dancer represents one of the instruments in the song for the same workshop inaugurating a new government theater in Shanghai. The “Water” show was performed both indoors and outdoors.

BOOKS BY TAMALYN

They Told Me I Couldn’t : A Young Woman’s Multicultural Adventures in Columbia

40 Days and 1001 Nights, One Woman’s Dance Through Life in the Islamic World

Belly Dancing for Fitness: The Ultimate Dance Workout That Unleashes Your Creative Spirit

DOCUMENTARY FILMS

While working on her book “40 Days and 1001 Nights,” Tamalyn Dallal started shooting footage to take her readers along with her. She’s continued to develop her skills as a documentary filmmaker through a range of projects.

40 Days and 1001 Nights (2007): The visual tale of 40 days in 5 different Muslim countries through the eyes of dance.

Zanzibar Dance, Trance and Devotion(2011): A look at 26 traditional dances from Zanzibar

Ethiopia Dances for Joy (2011): Looking for the roots of dance in the cradle of man’s ancestry

Pockets of Treasure: Traditional dances of the Deep South (in development; trailer edited by Laura Rose)

Global Development of Belly Dance (Future project)

CONTACT

For more information, you can reach out to Tamalyn directly through her dance or film web site.

Know of a belly dancer who needs her (or his) story told? Once a month, I’m blogging about dancers from the 1970s (and earlier) with the goal of educating and expanding audience for this incredible dance form. The selection process is entirely subjective. Please send suggestions to jcobrienbooks@gmail.com.

Previous dancers

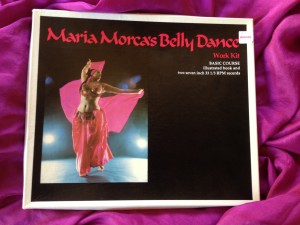

Have you ever wished a character in a book would just come alive and talk with you or teach you what she knows? Yes, it’s that freaking exciting. More than a decade later, I have the privilege of being coached by Maria Morca. Let me tell you about her.

Have you ever wished a character in a book would just come alive and talk with you or teach you what she knows? Yes, it’s that freaking exciting. More than a decade later, I have the privilege of being coached by Maria Morca. Let me tell you about her.