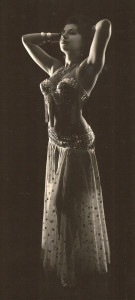

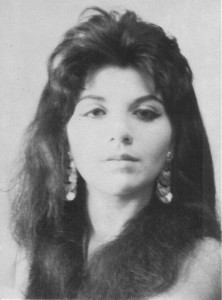

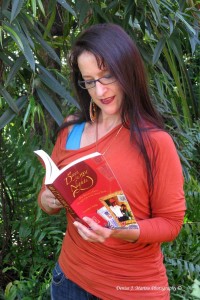

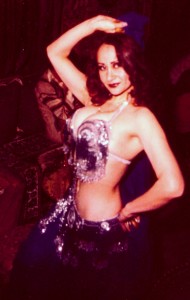

For the past two weeks, I’ve spent an embarrassingly large part of my practice time lying on the floor on my elbows trying to flip a quarter using my stomach muscles. I’ve gone from turning deeply red and drenched with sweat, to just sweat, but I’ve achieved the flip about eighty percent of the time. No, I will not be providing video. Instead I will dazzle you with the lady that holds the record for flipping nine quarters up and down twice, then one at a time up and down, then alternating quarters. Yes, belly dancer Helena Vlahos is in the Guinness Book of World Records for Unique Abdominal Dexterity.

While this trick has some serious wow factor, it gives you just the briefest hint of the control and grace Helena maintains throughout her entire body. At 67, Helena continues to flip coins, acquire new dance moves and teach with the patience, humor and skill that lead her to develop her signature trick – and made her a club favorite for over 50 years. She’s the reason why I’m cribbing so hard with that quarter. At the end of this month, Oriental Bliss Productions is bringing Helena to Seattle for a weekend intensive featuring workshops in Helena’s signature 6-part cabaret, sensual chiftetelli, abdominal technique and zils, plus a performance. (There might be some spaces left, click here for more info.)

From timid to at home on the stage

Helena Vlahos left her home in Greece when she was only eight-years-old. After growing up on an island without automobiles and more tourists than residents during the high season, Helena left “water so clear you could see the fish” to make a stop in Chicago before her family finally settled in Los Angeles.

In her earliest memory of the U.S., she talks about the city feeling “like kind of a jungle” with all the people walking around. Timid Helena would turn “red as a tomato” if a teacher called on her, but that shyness didn’t extend to the dance floor. “When my foot set on that stage, it changed me. I’m still shy in certain environments. It’s something about dancing that seems to be where I belong. It’s my home.”

Although Helena’s first teacher (and distant relative), Fofo DeMilo spotted natural talent “that everybody used to like” in Helena’s movements, her skills are the result of hours of practice, observation and breaking down the movements for her students.

In addition to teaching her the foundation moves such as hip movements, figure eights and arms, Fofo took 15-year-old Helena around to all the clubs so she could watch the other dancers and learn what worked and what didn’t in Fofo’s opinion. Fofo was opening the first belly dance studio in Hollywood and wanted her protégé to be stunning – and help with the other students. She used to say to Helena “Do you love the dance?” Helena says she didn’t know. She’d just started, but Fofo pressed on “You’ve got to love the dance.” As time passed on, Helena says she did grow to love the dance, sometimes, “you have to grow into it.”

Sixteen-year-old Helena debuted at the Athenian Restaurant in Los Angeles. When she was going around viewing other dancers, the MC got her up to dance and the owner liked what she saw and asked her to dance in the grand opening. Since she didn’t have a costume, she rented her something from the movie studios – a something with a very small bra and sparkly fishnet, but it could only be rented for three days at a time. So she was hired for three days. Helena wound up staying on for a year, working weekends for the likes of movie stars Rosalind Russell and Edward G. Robinson.

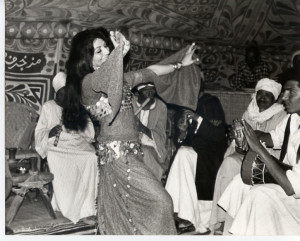

During the week, she danced in the Arabic clubs like Shakour’s Oasis among others and later moved on to dance at the Greek Village, Seventh Veil, Ali Baba’s, The Fez (see documentary clip and images below), and the Athenian Gardens in Hollywood.

Power: how to get (and keep) the audience’s attention

In addition to the advice to never date your club owner, musicians or customers, that Helena did not take to heart and resulting in significant heartache, Fofo taught her how to reach her audience through eye contact by knowing when and how and at whom to look. “What I learned later,” Helena says, “is that when you have the attention of one person, you have everyone’s attention, but it depends which person you pick” She advises that you ignore that rowdy one in favor of one “a little bit on the shy side and looking at you in awe. They will attract the eyes of everyone else on you because of their facial expression. This is what gives us more power in the dance. It just takes a few people to help us along in our dance. We’re not just alone. We need the other people to help us along.”

Getting musicians to work with you

In addition to the audience, Helena worked with musicians who helped hone her knowledge of the music and a few kind ones who helped develop her act.

In the mid 60s, Helena joined a group of musicians gathered by violinist Hrach Yacoubian to perform at the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas. Classically trained Yacoubian expressed his Armenian roots through a deep love for Mediterranean music. He liked to gather groups of Greeks, Arabs and Americans to create his own unique blend. “Everybody was afraid of him because we all admired him so much because he knew music so well and played the violin so well,” Helena says.

They played Greek and Arabic music as well as Turkish-influenced jazz like Blue Rondo à la Turk and Moscow Nights. In putting together the show, they rehearsed daily, including a head flinging bit that Helena performed regularly. Yacoubian expected the musicians the play perfectly timed to her flinging, but the musicians liked to count on the upswing. For Helena, it felt better counting on the downswing, which led to much discussion and even more rehearsal – so much so that Helena’s neck muscles grew so tired that she found her head wanting to rest on her chest. However, all the rehearsal paid off. At the end of their run, the Aladdin asked Helena to stay on without the band. But at 17, she felt she needed more experience and travelled on with the group to work at Yacoubian’s cousin’s place in Fresno – the Arabian Nights. While the musicians later went on to Bimbo’s in San Francisco, the owner’s wife preferred another dancer. Helena stayed on at the Arabian Nights for the rest of the year, becoming great friends with Yacoubian’s cousin Becky and her family.

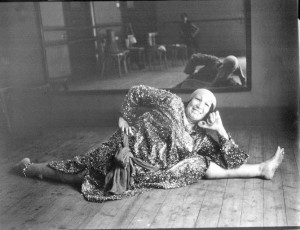

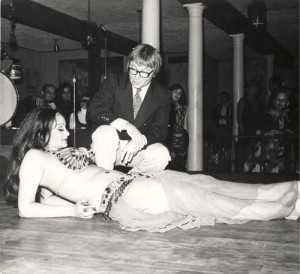

Helena’s famed belly rolls started in the studio when she was left to her own devices and was trying really hard but “couldn’t feel what I was supposed to do.” She says she was so nervous that she flopped down on the floor and pretended to quit. Once down there, she decided to give it another try. She tried and tried, finally felt something for the first time and propped herself up on her elbows so she could watch what her body was doing. From then on, she included belly rolls and flutters with her floor work.

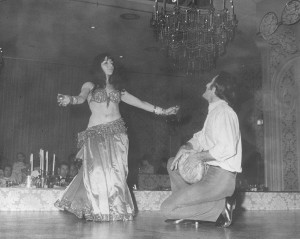

A huge influence was Khamis El Fino who played the oud and sang and understood the need to bring the audience along. “He would look at me and try to get as much out of me as possible to follow him.” Wearing a fez and pantaloons, this “great showman” would bring his oud over to play beside Helena during her floor work and belly rolls, playing faster when she fluttered, without ever taking away from her show.

Najib Khoury (formerly married to Antoinette Awayshak, a dancer and Suhaila’s ex-mother-in-law) would follow Helena’s belly work with his voice. “The ones that want to help you are part of your show and they create something really amazing with us.”

But Helena says she also learned from the musicians who wanted to steal her show, including a doumbek player who would “fight” with her musically on stage during the drum solo. He’d try to make his playing too hard to follow, she’d try to outdo him with her dancing. “Even that helped me a lot. You don’t learn dancing just by yourself. You have help from other dancers and from the musicians.”

When working with live musicians, Helena recommends informed respect and knowing your music and rhythms. “Bring the musicians into your act. Don’t act like they are not there, as if you are dancing to a CD. Acknowledge your musicians. Show them respect. As a solo dancer, you have to be in control of the stage. Never let a musician take over your show. Work with them to create a great show. It is your dance, your show. You should be in charge. This way you get the respect of the audience and your musicians.

Growing your act with your audience

The theme of working and learning from everyone around you flows throughout Helena’s career, but figures especially prominently in her signature trick. While on an off night from the Seventh Veil, the whole group was hired by the People Tree in Calabasas, Calif., dancing for a largely American crowd. When it came time for the floor work, the oud player came close and he was funny, so people would laugh and feel like they were part of the show. While Helena was rolling her belly, one of the customers decided to join in by placing a dollar on her belly. The bill caught in the folds and everybody grew very excited. Helena realized she was onto something and began practicing.

She learned to flip the bill up and down and long ways and crease it and open it again. Then she decided to try coins, testing every denomination, but finally settling on quarters.

First she worked with one, then decided to see what would happen with two. While rolling, one stayed put. She went with it and was able to make it happen when she wanted to. Then she added one more, then another as her muscles developed. After she’d been dancing for six years, she could do 9 quarters up and down twice, one at a time up twice each, every other one up and down and the remaining four together.

Achieving celebrity

Helena had relocated to Texas, achieving local celebrity dancing for several years at the Bacchanal in Houston and later at Zorba’s in Austin. When she returned to Los Angeles, one of her students mentioned her act to Regis Philbin, then of A.M. Los Angeles. Regis asked her to be on the show the very next day and a nervous Helena’s celebrity quickly grew. She ended up on That’s Incredible, The Merv Griffin Show, Mike Douglas Show and others, including the Spectacular World of Guinness Records TV Show. In order to be on that show, you had to have a record. Unsure how to register her act, they finally settled on “Unique Abdominal Dexterity.”

(I’ll vouch for that. Sit-ups will never make your stomach burn like trying to flip quarters. Fortunately, Helena tells me she’ll share some tips and tricks to make it easier during the workshop.)

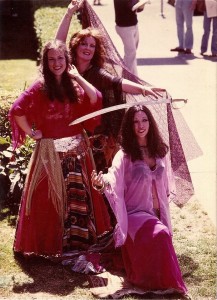

Learning organically; teaching technically

While Helena may have absorbed a great deal of the dance through observation, dancers in the 60s were expected to bring their zils with them and could count on being called up to dance at any time. You were considered “lacking” if you couldn’t play. Dancers were also expected to be versed in veil work, floor work, chiftetelli, bolero, 9/8 and 6/8. Helena’s sister Maria Vlahos, also a dancer, provided “very truthful” feedback. Not always what Helena wanted to hear, but always helpful. (Below is some rare footage of Helena and Maria Vlahos dancing at the Seventh Veil. The full clip also includes Diane Webber. While the image is quite dark and there is no audio, you can get a small taste of what dancing was like then.)

Helena spent a good deal of her time practicing and learned the hard way that playing the zils while sitting still could lead to trouble. “I used to play the music and try to keep up with the rhythms. I was practicing my zils separately from my dance. I used to sit down and listen and it was a challenge to me to see how fast I could go. A month later, OK I’m going to dance now with my zils. Biggest shock of my life, you can’t do that.” She says she learned how to dance with her zils through “trial and error” and with the help of the many musicians she worked with over the years.

Although Fofo did give her a foundation in the basics, teaching was not so technical then and dancer’s prided themselves on a variety of trade secrets. You would go to see so-and-so who specialized in belly work, another dancer for floor work, someone else for dancing with a great deal of emotion and so on. Each dancer had something unique to her that was a part of her show. And dancer’s guarded those skills like the trade secrets they were. So when a dancer shared a piece of advice, Helena says she treasured that information.

By the time Helena started teaching, students were used to asking questions – a great many questions – so Helena took what she had learned through observation and practice and learned how to break down everything from body part placement and posture to how to step properly with the downbeat. Today, Helena takes a special pride in teaching not only intermediate and advanced dancers, but beginners as well because she feels responsible for passing the dance along, especially to those who are dedicated and willing to learn her way of dancing which she says “can be a little harder.” Calling on her deep experience and technical knowledge she feels prepared to answer students’ challenging questions.

Dump the rules, keep the guidelines

As a judge for the Belly Dancer of the Universe Competition and while watching dancers on the internet and at workshops and shows across the country, Helena sees dancers influenced by ballet, modern dance and jazz. She says she loves the way dancers are dancing today because they know a lot more, but that sometimes dancers dance alike because they’ve been exposed to the same workshops and videos on the internet and worries that some people have developed too many “rules” for the dance.

“I hate when a dancer gives me rules. I am not following your rules. We’d all look the same.” One of her students in Arizona, a psychologist, helped her crystalize her concern: “You have to know when to do something and when not to do it. It’s not a rule; it’s a guideline. That’s what I believe 100 percent. What I’m telling you here is my opinion. Use your head. Use your own experience. Take what you want, throw out what you don’t.” Helena watches herself carefully. “I’ve had to eat my words,” she says, “when a dancer manages to make a move I’ve criticized look amazing.”

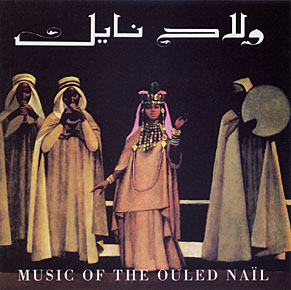

While belly dance has become more stylized over the last 50 years, Helena isn’t willing to leave anything out. I asked her what music a dancer should have in her collection and she mentioned Om Kalthoum because the music is so textured and fully orchestrated as well as Hakim, Sa’ad and the old standards like Aziza and Zaina, but she also says, “Collect as many [recordings] as you can of different singers, orchestrations. Don’t limit yourself to one thing. Variety, variety so you can pick different things, when you dance. I don’t believe in limiting when there’s so much.”

And while some dancers snub other dancers because it is not a style they dance, Helena scoffs at the need to snub dancers because they choose a different style than her own: “Do you mean to tell me that I can’t appreciate a dancer that is a really good dancer no matter what style? It may not be my thing, but that doesn’t mean I can’t enjoy a performance of someone who is good and has put so much time into doing it. We’re all in this. There are many types of doctors and a doctor is specialized in one or two things and you need them at different times for what ails you, but why not in dance? We can enjoy different things at different times.”

Cultural exchange

Which brings us to why we need dancers at all. Helena definitely sees the personal benefit to the dancer and to the audience in experiencing entertainment, but also sees the opportunity for unity. “Cultures take from each other, they borrow, they love and in turn they give their own in exchange. The purpose we’re serving is to connect with arts and music and dancing. It’s a better understanding than trying to understand people’s ways. Dancing and music is very beautiful for most people. Kind of a cure for loneliness, depression. Dance is a beautiful thing.”

RECENT PROJECTS

In the 60s, psychedelic rocker, Damon the Gypsy asked Helena to play zils on one of his albums. He recently remastered the songs and asked Helena to play again — and appear in his music video. They also performed at Amoeba Music in Hollywood.

STUDY WITH HELENA

If you’re in Seattle at the end of July, you can join me at the Helena Vlahos Weekend Intensive. She also offers classes in the Los Angeles area, as well as private lessons and workshops. Visit helenavlahos.com for more information or email her at helenavlahosdance@gmail.com or call at 818-618-9746.

[soliloquy id=”571″]

PRACTICAL QUESTIONS

How often do you practice? Not often enough. I practice when I teach and when I teach private students. That’s the time. I try to listen to music when I’m available and practice new things. Sometimes I want to try out a new move, so I teach to one of my really good private students and I show her, so by showing her, I practice. If I want to take that move and make it my own, I have to try and show her so I have to learn it. But I also do it on my own. I’ll think of a move that I want to try out and I want to see how it works or I play music that I’m going to dance to, so I play the CDs over and over and over in my car and then I try it at home. Not as often as I would like, but as often as I can.

What is the best piece of dance advice you ever received and who gave it to you? More recently when I was in Phoenix, Arizona, I asked the Sonia Valle, Director of Dance at Paradise Valley Community College who hired me to teach for-credit classes, what would you advise a dancer. She said, “Don’t anticipate the music. Wait for it to come.” In the back of my mind when I’m missing my cues. This is what I tell myself.

If you could whisper one piece of advice in every dancer’s ear, what would it be? Go out there and dance, and feel like the princes or queen that you are.

PREVIOUS PROFILES

Know of a belly dancer who needs her (or his) story told? Once a month, I’m blogging about dancers from the 1970s (and earlier) with the goal of educating and expanding an audience for this incredible dance form. The selection process is entirely subjective. Please send suggestions to jcobrienbooks@gmail.com. I also write supernatural noir, urban fantasy and horror. You can check out my fiction here (and yes, there is a belly dance book in the works).